|

| Of Piss @N' Pus, #5, 2002 |

|

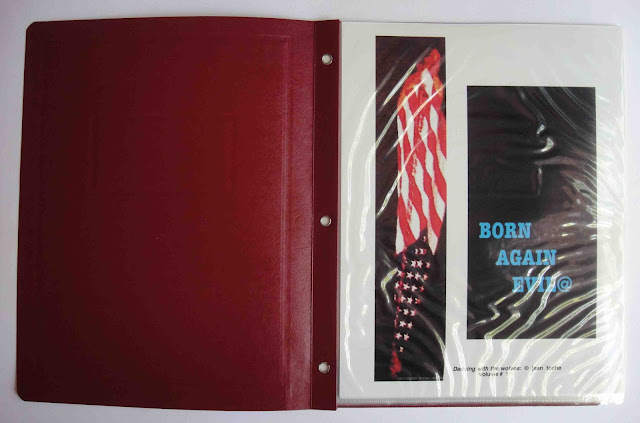

| Of Piss @N' Pus, #5, 2002 (inside cover) |

|

| Of Piss @N' Pus, #5, 2002 (inside pages) |

|

| Of Piss @ND Pus, #7, 2002 |

|

| Of Piss @ND Pus, #7, 2002 (inside pages) |

|

| Of Piss @N' Pus, #9, 2002 |

|

| Of Piss @N' Pus, #9, 2002 (inside pages) |

|

| Of Piss @N' Pus, #11, 2002 |

|

| Of Piss @N' Pus, #11, 2002 (inside pages) |

|

| Of Piss @N' Pus, #11, 2002 (inside pages) |

Twenty-five

years ago, when the Nazis fled from Belgium, my native country, after four

years of military occupation, I saw people burning in the streets all over the

country whatever had been German: books, magazines, records, films... Buildings

which had been occupied, or built, by the Germans were dynamited. The Belgians

wanted to erase forever whatever had been part of the Deutschland Kultur.

(Toche, 1969)1

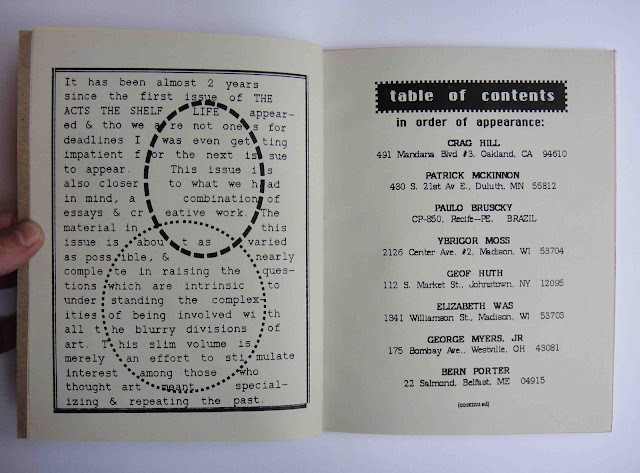

It's not easy being Jean Toche—at almost

eighty he's still waging war against the hypocrisy and stupidity of our

national and political culture. Since the early '90s, from his secure location

in Staten Island, he's been sending out bold, loud and outraged handbills that

contain his responses and suggestions for making things better, and how to keep

the bozos away from the levers of power. An exposer of fraudsters, poseurs, politicians,

hypocrites, government agencies and the art world, Toche started with single

sheets of text that were mailed out to around 50 people at a time, then he centralized

this activity in his artists' periodical Of

Piss @N' Pus (2002).2 Each of the periodical's 12 monthly issues

contain individually signed and designed handbills from a specific month. Using

quotes from mainstream media sources (New

York Times & Wall Street Journal),

Toche combines these with his own texts to critique, challenge and ridicule a

wide range of political and cultural events. These are serious and often

outrageous attacks on the body politic but they always contain a hint of humor.

Toche does not exclude himself from these critiques either. Each page is

printed on different colored papers, often with assorted pre-printed designs

and he creates different typographic layouts for each page. Bound together by a

removable plastic binder these original page works are presented in an

economical, and modest format that is in elegant contrast to the extravagance

of Toche's critiques and the challenges he aims at bombastic politicians and

their ilk.

At the same time as Toche started this periodical he was

encouraged by Jon Hendricks, a former artistic partner, to experiment with

digital technology. He acquired a new printer that enabled him to print works

up to 10 feet long and a digital camera and software with which he began to

create, and manipulate, an archive of self-portraits. It is from this latter collection

that he chooses the self-portraits in his now standard practice of combining digitally

manipulated self-portraits with his own and mass media texts. From

2002 up until quite recently he was printing his works in sizes that varied

from 6 - 10 feet long. Recent issues with the wholesale supplier of this

photographic paper has necessitated him working in a reduced format of 11"

x 8". Once again in order to streamline distribution of these works he has

adopted a folder format to distribute small groups of works. One of the first

of these publications I received from Toche was in May 2012 and it was titled Dancing with the Wolves, Vol. #1. Other

similar mailings have not included the periodical title, which suggests that Dancing with the Wolves might have been

a one-off periodical.

Toche also

has something of a history of intervening in situations in order to get his

voice and opinion heard. As one of the founding members, with Jon Hendricks of

the Guerrilla Art Action Group (GAAG, 1969-76), they communicated their views by

writing letters & sending handbills of protest to their adversaries, and

sometimes they created actions to draw particular attention to an issue.3

One celebrated event was the "blood bath" action that took place on

November 10, 1969, in the foyer of the Museum of Modern Art, in which Hendricks,

Toche, Johnson and Silvianna4 staged a fight in which the bags of

blood hidden under their clothes burst and splattered the participants. The text

that was left at the scene demanded the resignation of all the Rockefellers

from the board of trustees of the Museum of Modern Art because of their

involvement with the 'war machine.'

Four years

later the museums would get their revenge. On February 28, 1974, Toche, under

the auspices of the 'Ad Hoc Artists' Movement for Freedom,' sent a handbill to

assorted museums, newspapers and individuals in New York City in which he demanded

a number of things, including the kidnapping of museum "trustees,

directors, administrators, curators, & benefactors," and for them to

be held as war hostages until a People's Court could be convened to

"...deal specifically with the cultural crimes of the ruling class..."

Toche, with solidarity from the arts community, fought the kidnap charges for

more than a year before the government dropped all its charges.

Toche was 12 years old when he witnessed the events he describes

at the beginning of this text, and the powerful image of Belgium's WWII anti-Nazi

purge and the frenzied eradication of all Deutschland

Kultur provided a vivid experience of the power of culture and the culture

of power. Since his arrival in the US in 1965, Toche has waged his own war against

a culture he despises, and that's our culture of political corruption,

inequality and discrimination, to name but a few. However, one thing can be

stated with certainty—Toche's fight will be a fight to the end!5

Stephen Perkins, 2012

Footnotes

1. Jean Toche,

ltr. (Oct. 9, 1969) concerning the 7th Annual Avant Garde Festival, in GAAG: 1969-1976, Printed Matter:

New York, 1978, unpaginated: Introduction.

2. Various

issues of Of Piss @N' Pus have

different dates: #1-5: 2003, #7-12: 2002. Despite these different dates the

publication was published monthly during 2002. Confirmation of these dates can

be found in Kristine Stile's exhibition catalogue "Jean Toche: Impressions

from the Rogue Bush Imperial Presidency," presented at Duke University's

John Hope Franklin Center for Interdisciplinary and International Studies, Duke

University Center for International Studies, 2009. In footnote #5, page 14 she

states that she received the periodicals by mail from Toche and they were all

postdated 2002.

3. Other

collaborators and members of GAAG, were Virginia Poe (Toche), and Poppy

Johnson.

4. Silvianna

was an artist/filmmaker and participated in this action only, (in GAAG: 1969-1976).

5. Printed Matter in New

York has recently reprinted their invaluable 1978 sourcebook about GAAG,

titled: GAAG: The Guerrilla Art Action

Group,

1969 - 1976 : A Selection, Jon Hendricks & Jean

Toche, New York, NY: Printed Matter Inc., 2011. Printed Matter also has some of Toche's publications for

sale as well as copies of Of Piss @N' Pus #2 for $3. http://www.printedmatter.org/

An update: Jean Toche was found dead in his home by the police on Monday, July 9th, 2018, he was born in Breuge, Belgium in 1932.

An update: Jean Toche was found dead in his home by the police on Monday, July 9th, 2018, he was born in Breuge, Belgium in 1932.